What Essential Gear Should Be Prioritized for Long-Haul Alpine Expeditions?

Jan 10, 2026

There is a distinct shift in mindset that happens when you pack for a multi-day alpine traverse. You aren’t just throwing gear into a bag for a day hike; you are building a life-support system that you will carry on your back. Whether I am heading out with a rope team or stepping onto the trail alone, the process is always the same. I lay everything out on the living room floor—the stove, the layers, the medical kit—and I ask myself the question that defines backcountry travel: If everything goes wrong, is this enough?

The allure of the high country is its isolation, but that isolation demands a specific kind of respect. Moving through complex terrain requires a logistical strategy that balances the desire for a light pack against the reality of survivability. A sudden storm or a twisted ankle can turn a standard overnight trip into a prolonged survival scenario, and the gear we carry is the bridge between a mishap and a tragedy.

Building Your Systems

When professionals prepare for a traverse, they don't think in terms of individual items; they think in systems. For a multi-day objective, where pack weights often hover between 35 and 50 pounds, efficiency is key, but not at the cost of safety.

The shelter system is your first line of defense. Even if the plan involves sleeping in established huts, I always carry a lightweight alpine tent or a robust four-season bivy. The mountains are indifferent to our itineraries, and having the ability to survive a forced night out in the elements is non-negotiable. This pairs directly with your insulation system. It isn’t enough to be warm while moving; you need a high-loft down or synthetic parka that allows you to retain heat while stationary. If you are immobilized by injury or weather, that jacket becomes your primary medical device against hypothermia.

Calories are the fuel that keeps these systems running. On a traverse, the body burns through energy at an alarming rate. I plan for roughly 3,000 to 4,000 calories per day, focusing on dense fats and proteins. But the most important food in my pack is the emergency ration—the meal that requires no cooking and is saved strictly for the unplanned extra day.

The Reality of Remote Care

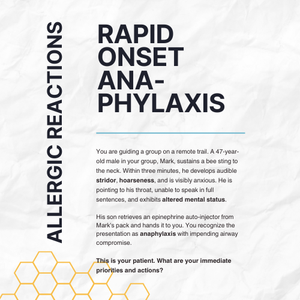

Perhaps the most critical component of the pack is the one we hope never to touch: the emergency medical kit. In a remote traverse, "rescue" is rarely immediate. Weather can ground helicopters, and ground teams may take days to reach a patient. We have to be prepared to manage care for the long haul.

Standard first aid kits are often insufficient for this environment. My kit is expanded to address the specific threats of the alpine: hypothermia, trauma, and immobility. This means carrying the materials to build a "burrito wrap" for a hypothermic patient—utilizing a sleeping pad to insulate from the ground, a sleeping bag, and a vapor barrier liner to trap heat. It means carrying a SAM splint and enough athletic tape to stabilize a fracture.

For the solo adventurer, this preparation is even more vital. If you are alone, you must be able to self-splint a fracture well enough to actuate your SOS device or crawl to shelter. Pain management becomes a logistical tool; consulting with a medical professional about carrying prescription-strength analgesics can be the deciding factor in whether an injured climber can self-evacuate.

The Safety Net Starts at Home

The most effective safety measures happen before we ever step onto the trail. Preparation is the silent partner on every trip. It begins with the Trip Plan—a detailed document left with a trusted contact in the frontcountry. This isn't just a note on the fridge; it includes the intended route, alternate "bail-out" options, vehicle information, and the specific "panic time" at which they should contact emergency services.

In the modern era, satellite communication has become the standard of care. Devices like the Garmin inReach or ZOLEO allow for two-way communication, which changes the dynamic of emergency response. Being able to text "I am delayed but safe" prevents unnecessary and costly rescue mobilizations. However, technology has its limits. Batteries die and GPS signals drift. Therefore, we must maintain the analog skills of reading a physical topographic map and compass. When a whiteout descends, these tools are often the only way to navigate safely to lower elevation.

The Solo Equation

Traveling alone in the alpine is a valid and deeply rewarding pursuit, but it changes the safety calculus. When I travel solo, my decision-making framework shifts. The threshold for turning around becomes much lower. If a route looks questionable, I do not have a rope team to arrest a fall or discuss the hazard.

For the solo traveler, frequent check-ins are a lifeline. Utilizing the tracking feature on a satellite device creates a digital "breadcrumb" trail. If I become incapacitated and cannot hit the SOS button, search and rescue teams have a starting point. It is a humble admission that while we may be capable, we are not invincible.

Whether we move alone or with partners, the mountains demand that we show up prepared. By packing with contingencies in mind and adhering to strict pre-trip protocols, we ensure that we are not just visitors in the alpine, but competent travelers ready for whatever the environment presents.

References

American Alpine Club. (2024). Accidents in North American climbing 2024. American Alpine Club. https://americanalpineclub.org/accidents-in-north-american-climbing

National Weather Service. (n.d.). Mountain weather forecasts. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved December 17, 2025, from https://www.weather.gov/

Northwest Avalanche Center. (n.d.). Avalanche forecasts and education. Retrieved December 17, 2025, from https://nwac.us/

The Mountaineers. (2018). Mountaineering: The freedom of the hills (9th ed.). Mountaineers Books.